Former Kraftwerk stalwart Karl Bartos has delved into his personal archive for his new album, ‘Off The Record’.The result is a futurist pop classic steeped in the past

“Who’s that person you were photographing? Is he famous?”

The question comes from a member of the hotel’s staff whose desk we have cluttered with light stands and other photography junk as we pack up after a quick photo shoot with Karl Bartos.

“His name is Karl Bartos, ” I tell her.

“He was in a band called Kraftwerk…”

No lights of recognition appear in her eyes.

“They had a song called ‘The Model’…”

Nothing. She’s interested, but she doesn’t know Kraftwerk. ‘The Model’ was a UK Number One hit more than 30 years ago, long before she was born.

“They make electronic music,” I say. “You could think of them as the Beatles of electronic music.”

“Wow!” Now she’s impressed.

“And Karl Bartos is sort of like the George Harrison of the band. Slightly overlooked, but a songwriter of real genius…”

And so here he is, in a London hotel, the George Harrison of electronic music, talking to Electronic Sound (named after George Harrison’s 1969 album of Moog explorations) about his new album, ‘Off The Record’, his first since 2003’s ‘Communication’. The interim has been filled mostly with his late career as a university professor, lecturing in sound design, or Auditory Media Design. It’s an entirely apt undertaking for a former member of the most intellectually hygienic pop group there has ever been. While he was talking about the work of Walter Murch to undergraduates at the University of Berlin, I wonder how many of them looked at their professor and excitedly thought, “You wrote ‘The Model’!”.

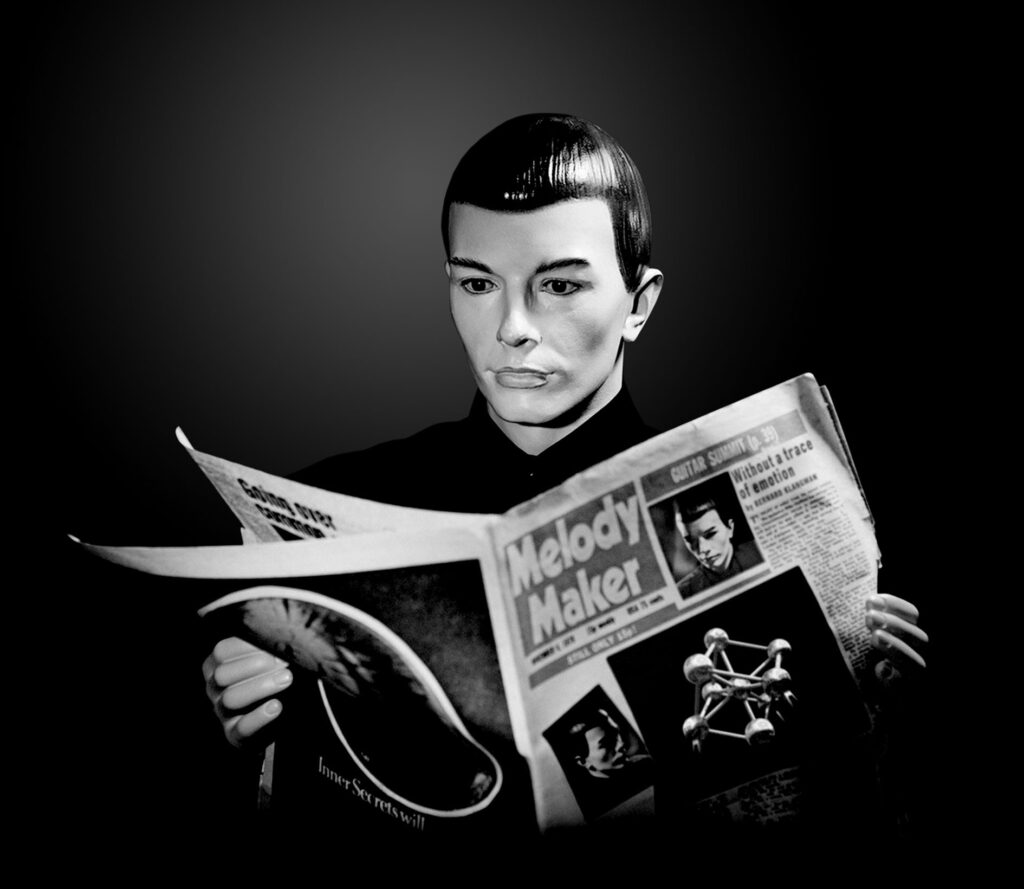

Karl Bartos’s new album is extraordinary for several reasons. For starters, there’s the artwork. It features images of his Kraftwerk dummy in various amusing poses; reading the once-great weekly British music paper Melody Maker; standing in front of a couple of studio speakers apparently conducting the music coming out of them; wearing headphones in front of a studio mic; holding a metronome; just looking plasticly handsome. It’s the enduring image of Kraftwerk: the showroom dummies, impassive, stiff, stylish, sinister, and yet ineffably humorous. It’s the first time an ex-member of Kraftwerk has made such a clear creative statement. Something along the lines of, “Kraftwerk? Classic line-up? Yeah, that was me.”.

Is ‘Off The Record’ a reclamation of his past as one quarter of the widely acknowledged classic Kraftwerk line-up?

“A re-conceiving, more like,” asserts Bartos. “I got this offer – was it a kind offer? I don’t know – from this label, Bureau B: ‘Hey Karl, have you got any old tapes in the attic?’. And then after several attempts from Gunther, who runs the label, I was convinced. Because it’s not the thing you want to do in your spare time. It’s quite a bit of work, going through an archive, opening all these boxes. It was a mess, basically.”

The tapes in Bartos’s attic date back through all of his musical career, including his time in Kraftwerk and beyond, and ‘Off The Record’ is a set of new songs inspired by and featuring melodies and beats pulled from his old demos. So it shouldn’t be a surprise that some of the tracks on the album sound like alternative versions of Kraftwerk tunes from ‘Computer World’ and ‘The Man Machine’ (the first two albums Bartos received writing credits for). ‘Rhythmus’, for example, uses the ‘Numbers’ beat from ‘Computer World’ and the opening synth refrain is so reminiscent of ‘Numbers’ itself that, well, it pretty much is the opening synth refrain from ‘Computer World’. This is, of course, because Bartos was a co-composer of those songs in the first place.

“I transferred all the data, the little cassettes – I had all the various formats – and sometimes I couldn’t read what I had written on them, but on almost every media I had the date, say 19 August 1977. I was quite lucky with that. Once I had transferred them into the computer, it took on an order by itself because of the dates, and so it finally arranged itself into an acoustic diary. I could do little cut-up things, even with compositions which are 10 years apart. You know, in the early days, you just had a drum machine running and a sequencer, and you played a motif for half an hour! In the 70s, this was the way to do it. And then once you had collected a couple of motifs, you used multi-track to bring it all together… magnétophone.”

The pre-Kraftwerk material is, he says, literally made up of jottings – ideas scribbled down with pen and paper.

“When I joined Kraftwerk, I started to record my ideas because I needed to evaluate my improvisations. Sometimes you just hit the button and hopefully you follow with one or two ideas you can use later.”

Where ‘Off The Record’ doesn’t sound much like Kraftwerk, and there’s plenty about the album that doesn’t, there’s still a thread of romanticism and almost childlike simplicity in its melodies. I suggest that this aesthetic of very easy-to-remember tunes, with uncomplicated constructions, is at the heart of Kraftwerk’s success as a pop group.

“I know what you mean,” nods Bartos. “It’s part of writing successful songs. They have to be remembered easily. In terms of instruments, for the first electronic productions we had just a sequencer and a drum machine, and you could play along doing some chords, but there was nothing else, and that meant simplicity. A sequencer was not polyphonic. It was just a monophonic bassline to start a track. So you had a basic rhythm, which you could not fool around with, the drum machine could only play a simple pattern. Maybe later you added a fill-in every 32 bars. What I’m trying to say is the kind of instrumentation lent itself to a straightforward form of composing. The media is always responsible for the content.”

The sound of old organ beatboxes are all over ‘Off The Record’. On ‘Vox Humana’, an elderly rhythm machine is put through its paces with a series of patch changes while synths burble and tinkle queasily, like a high-fidelity rendering of Cabaret Voltaire’s ‘Live At The YMCA’. The same, doubtlessly dusty machine is featured on the quaint ‘Hausmusik’, a jaunty nostalgia trip that harks back to Bartos listening to his mother and uncle playing Bavarian folk tunes on a zither, while heavy snow falls outside in the dark evening (I’m not making this up), a Teutonic equivalent of a singsong around the old joanna before television came along and ruined everything.

The feeling is accentuated by the Farfisa piano he uses on the track, which he describes as having “that perfect 8mm colour film sound”.

So did furtling around in dusty old boxes full of old tapes in the loft trigger this nostalgic wistfulness?

“Think if you go to visit your parents at home,” Karl says, spreading his hands wide like a storyteller, his eyes bright with amusement, “and your mother comes along with the Christmas turkey and later she opens up the box with the family photographs – ‘Oh look here, your first school day!’ – and she gets emotional and then nostalgia arrives… This is the feeling. It was really a mixed pleasure.”

This might be an especially German notion. It was brilliantly expressed by Kraftwerk on the ‘Trans-Europe Express’ album. It managed to synthesise a sense of modernism and forward motion with its intense electronic sounds and regimented yet funky beats, while simultaneously constantly recalling a semi-fictional but recognisably authentic European past. It was making fun of a stiff, Schlager-loving German traditionalism, with its imagery and styling, while also celebrating it. It was a trick Devo were to later pull off in a more American sci-fi manner with their ‘New Traditionalists’ album.

“With that album, everything fell into place,” Karl reveals. “We were strongly depending on our German European heritage. We had to make a distinction between Anglo-American music and ourselves. We didn’t belong to the blues generation, we’re not from the Mississippi Delta, and we weren’t from Liverpool. It’s not us. So we had a good look around us and we had to decide, ‘How do we really sound?’. I especially always felt in this tradition of futurism. If you study percussion, you sooner or later get acquainted with the futurism movement, which started in the beginning of the 20th century in Italy with Marinetti, and then got picked up by Schaeffer in Paris, and then by Stockhausen. It said that you can not only call music that which is played on a violin or piano or woodwind instrument. No, anything, any sound coming out of nature, technology or our surroundings, the ambience, if you organise it, could be music. Being a percussion player, I really loved this idea. By the end of my studies, I got really acquainted with the works of Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Cage, who built their career in the beginning on this perspective, and that was the junction between my life and Kraftwerk.”

And so Kraftwerk incorporated the sounds of a car journey, the noise of trains and metal-on-metal, and the voice of electricity to create their music, and by doing so managed to slip high-art concepts into pop music, almost unnoticed.

For Bartos, however, the most defining Kraftwerk album is ‘Autobahn’, recorded and released before he had been asked to join the band. “It is the most important record because it’s a blueprint, it’s all there,” he says. “But there is no sequencer on ‘Autobahn’. It’s all played by hand. The drums too. But it really doesn’t matter if it is played by hand or a sequencer. If it is slightly in time, it should work. And Florian did it very well, so he plays all the fast stuff on this record, the Steve Reich style part…’ He pause and hums the nifty fast synth line from a segment of ‘Autobahn’ around 18 minutes in. “Yes, I think it’s the most important record.”

It’s tempting to argue with him, but it would be like having a futile pub discussion about which Beatles album is more important, ‘Revolver’ or ‘Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band’. With George Harrison. And that, my electronic music-loving pals, would be uncool.

It’s not just me who insists on making Beatles references when talking about Kraftwerk. Karl Bartos’s own discourse is peppered with them. At one point he mentions his fondness for another great British 60s songwriter, Ray Davies. We talk about his former bandmate Wolfgang Flür’s pre-Kraftwerk group, The Beathovens, and we chortle long and hard about it. The name sums up the gauche innocence of German teenagers longing to ape their British counterparts and failing.

“It wouldn’t have been authentic for us if we would have played a Beatles bass, a Höfner bass – although it is German! – or a Ludwig set,” says Bartos. “I had all that, and had played it as a youngster in school. I got initialised by the music of the 60s because of the strong message, ‘Don’t trust authority!’.”

And there is the key to what Kraftwerk was. A band of musicians and thinkers who had their software coded, initialised as Bartos puts it, by British and American popular music, but whose classical training and exposure to the likes of Pierre Henry, Pierre Schaeffer and Karlheinz Stockhausen instilled a desire to define new sonic territory within an intellectual framework. It doesn’t quite explain how they foresaw the computer revolution with such accuracy and clarity, but what marks out most visionaries is their ability to see the overwhelming potential of new ideas to change the way people will behave.

After the interview, listening back to the recording, I realise how deftly Bartos had sidestepped my questions about the inner workings and inter-relationships in Kraftwerk. Once or twice, he pulled an imaginary zipper across his lips and grinned mischeviously. He did it when I tried to pick at the reasons why he and Wolfgang Flür eventually left the band.

Why does he think, in the end, Kraftwerk remain such an enduring proposition?

He ponders for a moment. “Every one of us in this room can remember hundreds of melodies. If we do a a quiz” – he hums the first few bars of Beethoven’s ‘Fifth Symphony’, and then a little of Mozart’s ‘Eine Kleine Nachtmusik’ – everyone knows these melodies, and these stick forever in our synapses in our brains. That’s why scientists consider definite pitch the most important parameter in music. And because we can remember it, it’s the only ingredient of musical composition that goes through the generations. We can write them down of course, but as soon as we remember them and sing them, they stick in our brain. A strong melody is the most important thing in composition, it’s like a signature tune for a TV station. It doesn’t have to be a long melody like in a symphony, where you cut it into pieces then you have the reprise. Beethoven could do it, but we have just three minutes and 20 seconds in a pop song. That’s why the Beatles are still in our minds. Because they were the masters of simplicity in their melodies.”

And that’s why Kraftwerk, the Beatles of electronic music, are still in our minds too.

Karl Bartos Glossary

Walter Murch

Walter Murch is the sound designer’s sound designer (he actually invented the term itself). His work is in full effect in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1974 film ‘The Conversation’, which is all about the recording of sound itself. They don’t make ‘em like that anymore. Murch later won an Oscar for his sound work on ‘Apocalypse Now’. He’s also a film editor – and he’s won an Oscar for that too (‘The English Patient’).

Schlager Music

A type of conservative, easy listening pop music (with regional variations), which is popular across the European continent with people who don’t really like music all that much. It has recently been enjoyed in a post-modern and simultaneously ironic and earnest way by young London hipsters wearing unusual shirts and facial hair. Tapete Records, an offshoot of Bureau B, last year released a compilation of 60s beat-infused girl pop called ‘Beat Frauleins’, some of which has distinct Schlager leanings.

Pierre Schaeffer

The inventor of musique concrète, a type of musical experimentation based around the idea that non-traditionally musical sounds, if organised skilfully using tape technology, could be considered a kind of music. Sounds, both recorded and found, are a ready-made source that just needs mixing and arranging in order to create musique concrète. Check out the link to listen to a 1948 Pierre Schaeffer piece, ‘Etude Aux Chemins De Fer’, which had a profound effect on the creation Kraftwerk’s ‘Trans-Europe Express’.

‘Off The Record’ is out on Bureau B Records