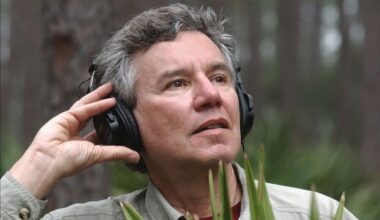

Superstar sonic boffin Amon Tobin has just performed his head-spinningly spectacular ‘ISAM’ live show for the very last time. Before he “takes it into the desert and burns it”, the revered master of sound and light talks about the genesis of the ‘ISAM’ concept and his unique approach to making electronic music an all-encompassing live experience

Brazilian-born, Brighton-raised Amon Adonai Santos de Araújo Tobin first appeared on the musical radar in the mid-1990s using a much shorter name. His one and only album as Cujo on London’s Ninebar Records, 1996’s ‘Adventures In Foam’, was quite enough to catch the ears of Ninja Tune, a label that has since then presided over the release of everything under the rather more manageable Amon Tobin moniker.

Ninja proved a natural home for Amon Tobin’s ever-inventive, constantly evolving, manipulated electronica. ‘Bricolage’ from 1997 is widely regarded as a stone-cold classic, Tobin’s complex compositions catching the ear of not only breakbeat aficionados but also a raft of jazz freaks, while his groundbreaking 2005 soundtrack to the ‘Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell: Chaos Theory’ video game was arranged so it could change in real time depending on the level of the action.

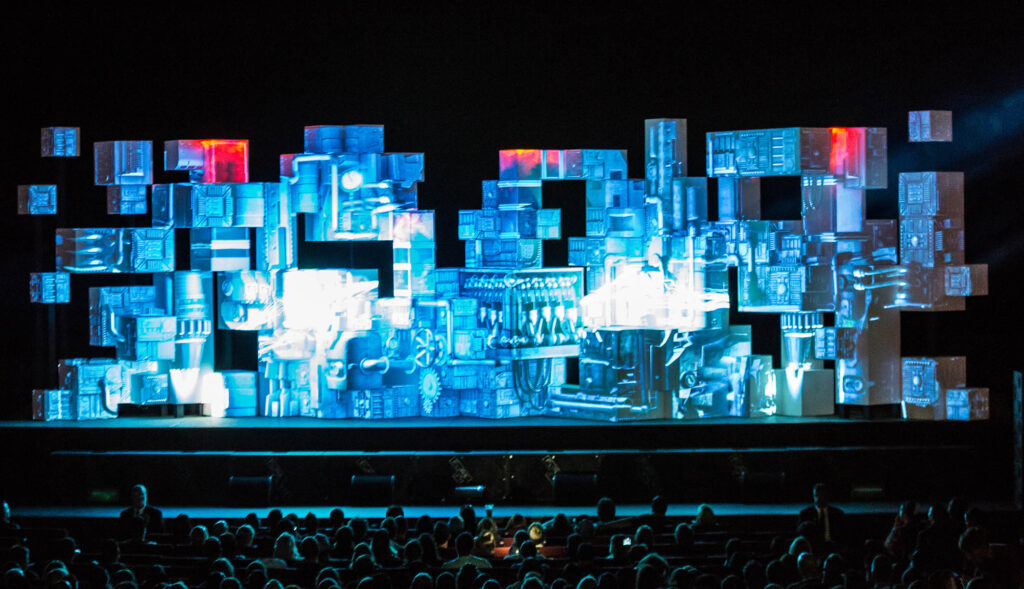

His live shows have followed a similarly innovative path, with Tobin choosing to present his music in a DJ format rather than taking live musicians on the road. But nodding along to his own tunes this is not. Starting in 2011, he took to the road in support of his acclaimed ‘ISAM’ album, performing inside an enormous purpose-built stage set that used the latest in video mapping technology to blow away audiences across the world.

With further tours and numerous one-off appearances over the last four years, the ‘ISAM’ shows (and the ‘ISAM 2.0’ update) have raised the bar for the live performance of electronic music – or any music for that matter – but Amon Tobin has just played what he says is the very last ‘ISAM’ show ever. And although he has said that before, this time it looks like he means it.

What does the concept of live electronic music mean to you, Amon?

“You know, even the terminology is weird for me. Live electronic music… it seems like an oxymoron. You can’t really play electronic music live.”

That’s quite a statement from the person who has probably done more than any other artist to redefine the live presentation of electronic music.

“I think it’s always been this amazing problem, at least coming from my background. When I started out, you’d go out and you’d DJ with some records and that was what it was all about. If there was any kind of performance, it would be on the scratch DJ side, they were the ones who were performing with records. People like me were mixing in a corner in a club and getting the crowd dancing. There was nothing to look at and everybody knew and understood that. That’s what DJing meant to me.”

So what changed?

“In the 1990s, we had the concept of the superstar DJ, so we found ourselves more and more up on a stage and, to be honest, it was a bit of a fish out of water situation. But somehow we all tried to make it work [laughs]. So everybody’s on stage playing records, and because you’re on stage people are looking at you… because why wouldn’t they? You’re on a stage! But you’re up there thinking, ‘Why are you looking at me? I’m clearly just playing records! This doesn’t make any sense!’. To me, it seemed like the biggest square peg in a round hole. The idea of thousands of people watching a guy playing records, I kept thinking it was crazy and something had to change. And then you started getting other artists using their laptops and trying as hard as they could to look like they were doing something. But even so, you know, watching someone fiddling around with a laptop on stage is about the least compelling thing you can imagine.”

A laptop on a stage is never a pretty sight.

“The whole thing seems completely counter-intuitive to me, it really does. Which is why, when I did my ‘ISAM’ album, I didn’t think there was any way I was going to be able to perform it live. I got into a particularly difficult spot because ‘ISAM’ wasn’t a DJ record, so as well as there being no way that I could really share it in a live environment, I also couldn’t share it in a DJ environment. I had to try to come up with something completely different, a way to present music that wasn’t dance music but was still electronic. So not live show and not a DJ set, but a sort of, I don’t know, a performance… film… thing… that worked with the music of the album and was visually engaging because it was happening on a stage.”

The ‘ISAM’ show seems to have been defined as much by what it couldn’t be as what it might be…

“Right. Clearly not a DJ show. And not about the podium DJ either.”

Did the people you approached to help you put the show together immediately understand your initial idea?

“No, it took some discussion to get that across. Even when I first started talking to Heather Shaw [CEO of Los Angeles design company Vita Motus], who designed the cube things, her first sketches came back and they still had me on a podium in the middle. Which makes sense, of course. I mean, you’re the DJ, you’re going to be in the middle, right? I had to say, ‘No, inside the cube please, not on it, and I’m not going to appear at all throughout the whole show’. The promoters weren’t too keen on that, let me tell you!”

You really wanted to be inside a structure?

“I was just trying to think of different things. I’d seen Richie Hawtin had that awesome set-up for his Plastikman set. Alright, it was transparent and the visual aspect was fairly abstract, but I did really like the idea of being inside something. So I tried to find ways I might be able to do that. I looked at different emerging technologies, some mechanical stuff, stuff with strobes, stuff with different surfaces… oh God, I can’t even remember now. In the end, I sort of stumbled on projection mapping through endless YouTube searches, and then I had to try to find the people who could actually do the mapping, and they had to then find the people who could develop the software to do it in a practical amount of time.”

Projection mapping is a method of projecting images precisely onto various surfaces using software to control the projections. That’s right, isn’t it?

“Yeah, it had been around for a while in the world of corporate and civic events – you could go and see the Eiffel Tower lit up or some old building falling apart and coming back together – and it was all a very city-centre-on-New-Year’s-Eve type of a gig. I thought if could find a way to turn something like that into a stage show, that could really work, because it had an animation to it and I could then tell a little story through it, and have the focus of the show on the visual interpretation of the music as opposed to being on the performer. To me, that was the key to it.”

And you wanted to build this enormous structure in a new venue every night?

“That was the other thing. At that point, the big shows in the city centres took weeks to set up and line up where images were mapped to, so on a tour where you’re going to be in a different city every night, we had to figure out how to do it in roughly four hours. And that took a lot of development from people like Leviathan [Chicago-based conceptual designers], who figured out how to do that. It was a real collaborative effort, finding people who had the technological know-how and skills to realise what I was trying to put together.”

There must have been points where you wondered whether it was ever going to work? Did you also worry that it was going to cost a lot of money?

“There was so much to do and we really didn’t know how it was going to turn out. Everything was complete guesswork, including what it was going to cost. Kudos to Ninja Tune for fronting the money for it. I didn’t have the money for it and I couldn’t get any sponsorship, no fucker would sponsor me, so Ninja advanced it. Obviously, I paid for it in the end [laughs], but they had enough faith in the ‘ISAM’ album and the whole idea of the show to take a gamble with me on it. That was a huge thing and I couldn’t have done it without them.”

Were you involved throughout the whole process?

“People often have this idea that I hired a company and said, ‘Make me a fantastic show’, and off they went. Actually, it was very different to that. I was very much directing every stage because I was so nervous about it. There was so much was riding on it, I felt I needed to micro-manage every single aspect of it. I set out how the show would flow in terms of the music, then I storyboarded each track with a theme and a colour scheme. I did that with Vello Virkhaus [from Californian multi-media production firm V Squared Labs]. We spent a couple of nights going through each track and I told Vello the story I’d made up in the park the previous afternoon – some ridiculous teenage fantasy about going into space and getting hit by a meteorite and seeing aliens and how the aliens are actually you… It was a pretty trippy idea.”

Was the overall narrative tightly scripted?

“It was actually very vague, which was important in the end. A lot of what made it work was to do with the pacing of the show. It wasn’t just about having a big flashy thing on the stage, it was about having every moment that happened lead into something else logically, and then pacing the sounds and each new visual well enough that they didn’t linger too long but weren’t over too quickly, and having enough detail that you could see new things if you went to see the show again. This is the sort of approach I usually apply to arranging music, so I applied it to the show as well. It was a whole process. And we didn’t know how people were going to react. We didn’t know if the space would be dark enough, or if people would be too close so the illusion wouldn’t work, or if they’d be at the wrong angle… It was really nail-biting.”

Do you think ideas like logic, narrative and drama are missing from live electronic music?

“Yes. Even V Squared were coming back with things like sea creatures and bouncing balls, and I’d be looking at these images and asking, ‘Why is there a fucking dolphin flying around? What’s going on here?’. There has to be point to what’s going on or it’s just eye candy. There are any number of shows where you have this amazing production, but in the end the content is effectively a series of screensavers or fancy-looking images that don’t make any sense.”

Do you think your audience understood everything you were trying to do?

“Mostly, but I did get some critical comments from people who were expecting a more traditional show or had been to see Daft Punk or… who’s that mouse guy?”

Deadmaus?

“Yes! Him! I was getting comments like, ‘Why can’t I dance to this? Where’s the beat? This show looks great, but it would be so much better if the music was like Deadmaus’. But the whole point was that it wasn’t a club show. If it was, if it was just about dancing, why put something massive on stage to look at?”

Your music has always had that tension between being dance music and lifting off into explorations of the nature of sound.

“It’s personal taste. I like techno and I like drum ’n’ bass, but I separate them out. I have another outlet called Two Fingers, which is really just music for DJing. With that, I try to play small venues where I can set up with Traktor or whatever and just play beats for people to get down to. It’s really good fun, but my Amon Tobin stuff wouldn’t work like that.”

Some time ago, you said you were going to burn the cubes in the desert. You obviously didn’t do that because you’ve just played what was billed as the last ever ‘ISAM’ show at the Outside Lands festival in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park.

“Yes, the last ever show… again [laughs]. I really didn’t know how that was going to go. It had been a long time and I was worried it might look dated. But it seemed kind of fitting to do it there and people were asking for it, so I figured, OK, one last show and then I’ll move on to the next thing. I’m already on to the next thing, actually. I’m working on it now, but it will take some time.”

Can you tell us what it is?

“Until I have it all in the bag and I know it’s going to work, it would be a bit silly to talk about it. But I do feel that, in general, the idea of these stage shows getting bigger and bigger isn’t that exciting or interesting. it would be alright if there was a point to it, but at the moment I just keep seeing enormous productions without any compelling content.”

So are you heading in the opposite direction now?

“I’m almost hoping for a backlash against the massive shows because they’re all so bloated now. As a music fan, I feel I would be a bit turned off by going to a big stage show. I’d be more interested in seeing something more intimate, or if it’s going to be something big then it needs to be in a different format, not just a huge thing you go and stare at.”

Have you seen Kraftwerk’s 3D show?

“I haven’t, no. I really envied them sending the robots out. Genius!”

The 3D performance is fun. When you look around at everyone wearing the 3D glasses, it’s like being in a 1950s cinema or something.

“Excellent!”

Although when I first heard about the ‘ISAM’ gigs, it did occur to me that Kraftwerk needed to takea look at what you were doing.

“It’s funny how it’s become an arms race, right? The stage shows are all very competitive but I don’t know that it’s particularly healthy because it just takes things further from music. It becomes about who has the most money, who can invest in something truly spectacular. It would cost an enormous amount of money to come close to topping anything that you’re seeing out there at the moment. It concerns me that there are new kids coming up with really good music, artists who are not necessarily fitting into the club format, they’re not making dance music, and they don’t have a platform because they can’t compete with these ridiculous stage shows. It does all seem a bit corporate, a bit money-driven. I do feel that if it gets to the point where your audience is limited by your financial reach, that’s inherently wrong. I also think that’s got a lot to do with the way music is listened to and consumed now.”

You mean streaming and downloads?

“Well, yes. I think this problem could have been entirely sidestepped if the music industry hadn’t gone the way it has in the last 10 years. The fact is that there’s always been a lot of music that was experimental and wasn’t necessarily ever meant to be performed. The problem is that now music is basically free, the main source of revenue for an artist is playing live. It’s the only way artists can support themselves. So that factor looms over all of us. If you’re not going to sell this music, you have to perform it, and so the performance issue has become much bigger than it otherwise would have been. I don’t know, I’m talking like an old man! I’m not saying things shouldn’t be how they are, or any of that shit, I’m just wondering how much that affects the situation we’re in. How would things be if the emphasis was less on performances and more on the actual music. A lot of this is only an issue because we all have to go on stage, so we’re wracking our brains about how the fuck to do that when we don’t play instruments [laughs].”

Maybe it’ll take someone with the brass neck to create something like, oh, I don’t know, ‘ISAM’ or ‘ISAM 2.0’, maybe?

“Foolish enough. But we need more fools.”

Well, I wasn’t going to say that. Anyway, it’s worked out for you. But you have rather torpedoed our idea of exploring how electronic music works in a live context…

“Sorry about that. It’s true that it’s an odd thing, but that’s the reality [laughs].”

Thanks Amon. That’s probably a good place to leave it.

“It probably is, isn’t it? Good speaking with you.”