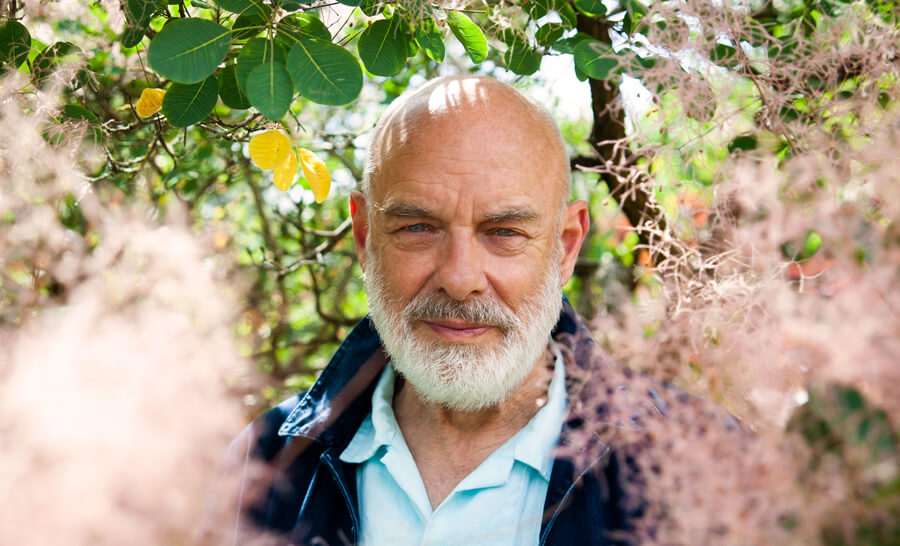

Generative film exploring Brian Eno’s creative life

If there’s going to be a documentary about Brian Eno in 2024, then it should certainly have a piece of software with it that somehow generates a unique edit each time it’s screened. This simply titled doc ‘ENO’, with its clever generative twist, is from celebrated filmmaker Gary Hustwist, whose CV is filled with excellent films including the Electronic Sound favourite ‘Helvetica’ and ‘Rams’ about the designer Dieter Rams.

For all the high faultin’ nature of those impressive docs, Hustwist has a background in underground music, specifically with the punk label SST when they were putting out records by Sonic Youth, Black Flag and Dinosaur Jr. He has the reference points required to capture a subject like Eno, whose shapeshifting work slips between the academic and popular without notice.

Blink-and-you-miss-‘em postage stamp-sized snippets of Eno alumni tile across the screen: Devo, U2, Laurie Anderson, Bowie, Roxy… The date and location of our showing (3 July, 2024, London) pings up on the screen hidden in a scramble of hack-the-mainframe computer code and file names, with a suitably sci-fi sonic squiggle to accompany it, and we’re off into Eno-land.

The interjections of graphics and images make up the edit points which, I assume, is the software doing its generative thing, randomly selecting the next nuggets of Eno wisdom, recollection and archive footage.

And very illuminating they are too. We see the importance of his rural upbringing in Suffolk which left him with a fascination for rivers (in constant motion, rushing somewhere, en route to another place, but at the same time always there), his love of nature and gardening, his excitement at a cluster of spider eggs on a leaf which one day dropped to the ground and resulted in a scattering of little creatures. His metaphor for his creativity is planting seeds, and then allowing them to grow without too much interference.

There’s a satisfying amount of time spent on Roxy Music, with some fine interview snippets with him in full Eno-pomp; glam make-up, feathers and extravagantly weird hair. At one point an interviewer, maybe in the early 90s, asks him if he’s embarrassed seeing his former self’s peacock rock star phase. Eno laughs. Not at all, he says. He’s never embarrassed. He’s upset sometimes, like when he describes recording a track for a 1970s solo album with tears rolling down his cheeks, burdened with deadlines and a pricey studio burning through cash. But even that was a learning experience, where he twigged that his emotional state while making music does not necessarily correlate to the output he produces.

His whole process is one of questioning and then framing answers that allow him to move forward. Why do I feel like this? Why do humans like music? Why do we like some music better than other music? He expounds his thoughts on art, music and life, gamely playing excerpts from his hours and hours of dictaphone recordings of his sketches for vocals, and his diaries. What comes across is that all of it, the note taking, the lectures, the productions, the work itself, whether it’s light sculptures (the section on how he realised he could use a video camera and televisions to create light, and then placed tubes on an upturned screen to make slowly self-generating light sculptures is particularly fun) or writing songs with John Cale, or singing with groups of people, creativity comes when he’s playing, like a child. The inner critic, which he also has in abundance, can wait until the next day.

There’s a scene where he and Daniel Lanois are helping Bono find the song when committing ‘Pride (In The Name Of Love)’ to tape. “Maybe more emotion next time,” Lanois cracks, “Try singing it standing up.”

Bono comes into the control room to listen back. It somehow still doesn’t sound grand enough, he complains, as The Edge flicks through a magazine.

“We could try slowing it down,” Eno suggests, and waggles the varispeed around a bit. And voila, after a few comical moments, there it is, the anthem of a generation.

Even as he expounds on his ideas about ecology and the human brain (it’s getting smaller, apparently, he thinks this is because we’re specialising and no longer need to know how to multitask with life or death hunter gatherer urgency) humour is centred. A fly interrupts the recording at one point, buzzing infuriatingly loudly on the microphone. “I ran out of fly killer unfortunately, and I broke my fly swatter. Violence is the only language they understand…” Or when he’s in a park talking about the evolution of creativity, he realises the spot they’ve chosen is where professional dog walkers gather. “Fucking walk them then! Don’t just stand around here!” he jokingly fumes. In another archive interview, a snippet with Paul Morley wearing a suit with none-more-80s shoulder pads, he mentions his father was a postman, and his grandad, too.

“Why so many postmen?” quizzes Morley.

“It’s a good job. A steady job,” Eno responds, then chuckles. “That sounds like a David Byrne lyric. ‘A steady job… in small town…’ he sings, with Byrne’s jerky prosody. We also see self-shot video footage of Eno, probably in his late 1970s New York phase, rehearsing moves and facial expressions which look very much like ideas for Talking Heads presentations, and he expounds on how when he first heard Fela Kuta’s music, he thought he’d caught a glimpse of the future, and knew he had the blueprint for the new Talking Heads album he would produce, the paradigm-shifting ‘Remain In Light’.

Bowie turns up, of course, archive footage of him saying he’s really not sure exactly what it is Eno does, but then going to define it as elegantly as only Bowie could. And you can imagine Bowie laughing like a drain at Eno’s anecdote of the time he decided that Marcel Duchamp’s famous urinal needed bringing back to reality by pissing in it. It was behind glass, but with gaps in the panes, sadly “not large enough for my organ” but he worked out that he could squeeze a plastic pipe filled with his piss through the gap.

So that was our Eno, 3 July 2024, London. Your Eno will be different. Your Eno may have produced that Coldplay album. Our Eno made ‘After The Heat’ with Moebius and Roedlieus. The point of the self-generating nature of this film is that you can drop in at any point in Eno’s five decades of cultural contributions, in any order, and there Eno will be, having fun exploring creativity, doing something that interests him. And it’s all the same, but different. Like the river he grew up playing around in.

The Eno soundtrack is released on vinyl and CD on 14 July. Order or listen here