In 1981, when Chris & Cosey left behind the stresses and strains of Throbbing Gristle, they finally found the time and space to breathe out. The new direction they forged could have seen them heading for ‘Top Of The Pops’, but they were determined to do everything on their own terms. Forty years on and the dynamic duo are still doing it their way

“We were happy to bounce off one another, rather than having to consider the image of Throbbing Gristle, the sound of TG, me not being allowed to do vocals in TG,” says Cosey Fanni Tutti. “It’s a cliché, but suddenly I had a voice. I feel my own body wanting to make sounds when I’m in the recording studio. And in TG, I couldn’t always do that, I couldn’t presume to make those sounds, so it was very frustrating for me.”

Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti are speaking from their home in rural Norfolk, far away in time and place from the madding, industrial stresses and strife from which they first emerged in the 1970s. They discuss their history and their travails, from their time in Throbbing Gristle to their work as Chris & Cosey, with an almost homely matter-of-fact-ness – the warm, calm and reflective tones of a couple who have truly found peace.

As we have learned from her 2017 autobiography, ‘Art Sex Music’, Cosey suffered far more from the internal pressures of TG than the group’s fans realised. Much of that was due to the intolerably exacting Genesis P-Orridge, with whom Cosey was in a relationship that was both emotionally and physically abusive, and for which she herself wrongly assumed the burden of guilt. Her relationship with Chris Carter couldn’t have been more different, however, offering the couple much-needed emotional respite and pointing away from TG in a new artistic direction.

“We had no constraints once we got outside of TG,” says Chris. “We were joyous and happy. That’s reflected in the Chris & Cosey albums.”

“There was no darkness there, no conflict,” agrees Cosey.

Not that their 1980s and 1990s work as Chris & Cosey was a lovey-dovey outpouring of soft-focus pop. They didn’t entirely shed the abrasion and abstraction of TG, hard-wired as it was into their history and foundation. They always posed challenges, for themselves and for their audiences. Mainstream success could easily have been theirs, but they preferred to maintain their creative scruples, as well as a certain X-rated licence, rather than acquiesce to commercial demands.

At the same time, they chose to morph when they could have stuck to the same tried and trusted formula. Forty years on from the first Chris & Cosey record, with their popularity seemingly still growing, the duo’s back catalogue writhes with the forbidden joy of physicality, daringly beautiful from start to finish.

Despite the aversion of the technophobic Genesis P-Orridge to machines – “You’re just a knob twiddler!” Cosey remembers him jeering to Chris – they were crucial to the duo from the outset.

“Electronics democratised sound for women because it wasn’t genderised in the way a guitar is,” says Cosey. “The axe, the phallic symbol…”

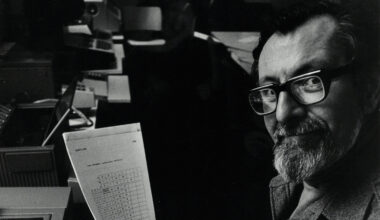

“I was aware of synthesisers from the late 1960s,” notes Chris. “I was collecting brochures and buying copies of Practical Electronics, a DIY mag that featured synth circuits. I was looking forward to engaging with synths, but they were out of my reach, I was too poor to afford them, so my way in was to build things myself. I had tape recorders and cassette machines and a drum machine. This drum machine was enormous, although it was very basic. I bought it in a second-hand shop. As for the Moog and the ARP, they were about 10 grand… and you could buy a house for that.”

“Two houses!” laughs Cosey. “People today don’t understand. Everything is so accessible nowadays, so cheap, which is great because anybody can use a synth and experiment with it. But back then, the innovations we came up with were because we couldn’t afford stuff like that.”

“It all changed when the first Japanese synths came in,” continues Chris. “They cost hundreds, rather than thousands. Mind you, even that was a lot for me. I still had to do it on hire purchase. I got a VCS 3 very early on and it cost me £350. I’ve still got the receipt. I couldn’t keep up the payments, though, so I only had it for a couple of months before I had to give it back to the loan company. My first synth in TG was a miniKORG. I also had a big monster of a machine I built myself, but I needed an off-the-shelf synth that played proper notes… and stayed in tune.”

These were also the years of heightened synthophobia, when pioneers like Chris were not considered to be authentic musicians and were subsequently deemed ineligible for the Musicians’ Union, who had their own fears about new technology.

“There were two things going on at that point,” explains Chris. “There was this fear that synths were putting people out of work because they had presets for violin and trumpet, and the Musicians’ Union assumed you pressed a button and got a violin or a trumpet, whereas the presets sounded nothing like those instruments. And on top of that, there was the ‘Home Taping Is Killing Music’ campaign, which fed into this general reluctance and suspicion about electronics. ‘I Feel Love’ was the moment that people began to take it seriously. All of a sudden, you could make a pop hit with synths.”

Alongside this wider appreciation for electronics came a fresh approach to the creation of sounds. Making music was no longer about training or virtuosity, about elaborate soloing or guitar heroism. It was also about thinking conceptually.

“I really embraced Eno’s idea of being a non-musician, even though I was technically playing an instrument,” says Chris.

Given her background as a performance artist with the collective COUM Transmissions, it’s something that also appealed to Cosey.

“I liked the thought of that because it was an unknown – and I love the unknown,” she says. “It was a way into something without having to go via notation, or anything else for that matter. Chris talks about wanting to stay in tune, but I wasn’t really interested in doing that.”

“Because you’d had piano lessons,” interrupts Chris. “And no one else in the band had.”

“Sleazy had,” counters Cosey.

“Really?” says Chris. “He was rubbish on keyboards.”

“He was rubbish on rhythm too,” says Cosey, before continuing to make her point. “Electronics gave me access to making sound on, well, machines really, but they worked as instruments for me. I always want to have a physical relationship with an instrument. I could never get into synths the way Chris does. He’ll go into the studio and he’ll be in there all day if you leave him. Whereas I want to get hold of something until you reach a point of satisfaction with it, like you do with any physical contact. You get to that point where you think, ‘Yeah, that’s great’. I had to have that connection, with my body controlling the sound. A physical loop.”

Although Cosey played guitar in Throbbing Gristle, she demanded that it be plugged into the electronic machinery and modified as a result. It was part of TG’s overall mission to deconstruct, to decondition.

“I just wanted to hook everything together, to let them all talk to each other and see what they come up with,” she says. “I didn’t want to know how they worked. I just wanted to hear what they could do.”

“It’s the same as driving a car,” adds Chris. “You don’t have to know how a car works to do that.”

“Yeah, but when you’re driving a car, you’ve got the Highway Code,” says Cosey. “I didn’t even want to know the Highway Code.”

While they were trailblazers in the context of the 70s rock scene, the ideas propounded by Throbbing Gristle had their precursors in the 20th century avant-garde – the notions of the art of noise, “machine music” and “machine art”, as propagated by the Futurists and Dadaists respectively before and during the First World War – and in the use of electronics by the likes of Pierre Schaeffer and Karlheinz Stockhausen, a radical antidote to conventional notation and muzak.

The band’s stark, existential provocation, a world away from mere entertainment, again had its antecedents in Dada and also the Fluxus movement. How aware were Chris and Cosey of these in the back story of electronic music, as well as 20th century art history overall?

“At the time, I was really into prog rock,” admits Chris. “I wasn’t aware of musique concrète. I wasn’t even aware of people similar to TG, like Can.

They just weren’t on my radar. I was into krautrock to a degree, but more the electronic stuff. And the rest of the band were into Frank Zappa, The Velvet Underground…”

“I don’t think I ever wanted to emulate what I listened to in my downtime,” says Cosey. “I wasn’t interested in sounding like anyone else at all. My interest in music has always been quite selfish. I wanted something out of it that expressed how I felt. And rock ’n’ roll didn’t do that for me. That was someone else’s self-expression. I was listening to a lot of chart stuff like Donna Summer while I was dancing professionally every day, so when TG did tracks such as ‘Hot On The Heels Of Love’, that was the zone I was in.

I’ve always been into melody, as well. Melody, rhythm and vocals are my thing, which I suppose is why we formed Chris & Cosey.”

The vaulting proto-synthpop of ‘AB/7A’ on TG’s 1978 album, ‘DOA: The Third And Final Report Of Throbbing Gristle’, and ‘Hot On The Heels Of Love’ on the following year’s ‘20 Jazz Funk Greats’, with its arpeggiated velocity and Cosey’s breathy, performative vocals, seem like statements of autonomy from the pair. With hindsight, they’re almost the first breakaway gestures, a hint that the end of TG was nigh. But despite everything she had suffered at the hands of Genesis P-Orridge, Cosey still hoped the group had a future.

“I harboured the belief that we were all adults and we could have carried on with TG,” she says. “I didn’t want it to end just because of a personal break-up. At the time, I didn’t know about the rumblings in the background.”

“I instigated the split,” explains Chris. “I’d had enough and I thought it had run its course. It didn’t mean as much to me as it did to Cosey and Gen.”

These crossover years, which saw Chris and Cosey leave behind their Industrial record label as well as TG, were busy – out of both practicality and artistic necessity. Cosey juggled a compulsion to create with a parallel career working in porn films and as a stripper, partly as a real-life (if at times scary) manifestation of her performance art, but also because the cash-strapped pair needed the money.

“It was an incredibly frantic time,” says Cosey. “I was gobsmacked at how much I did every day. I never stayed still. In the evenings, I was doing the modelling, the film work, and then there were the gigs… it was totally nuts. There was no time for drugs, for getting out of your head. I’m amazed I didn’t have a nervous breakdown. The 1970s was like film noir, with psychedelic moments. The 1980s was nice pastel colours, all cleaned up. It was like we’d had to get everything dirty for the 80s to happen.”

“We signed to Rough Trade and they were really good with us, really supportive of what we did,” says Chris. “We left TG and Industrial with nothing. Everything, including the finances, stayed in the TG camp, so we had to start again from scratch. We had very little gear and we were living off Cosey’s stripping earnings.”

Despite this, Chris & Cosey basked in the warm glow of their post-TG freedom. For all the lingering friction of their 1981 debut album ‘Heartbeat’, there is a definite feeling of being unleashed from the traps. ‘This Is Me’, for example, announced by a joyful blast of cornet, hurtling and scampering towards liberty, as if the pair are dashing barefoot through a cornfield like emancipated lovers, or ‘Here I Come’, where they are at last able to speak and sing as they please.

The Chris & Cosey albums of the early 80s would run the gamut of styles from the more experimental, artfully sculpted electronica they would never abandon, to out-and-out clubland synthpop tracks like the shining ecstasy of ‘Walking Through Heaven’ from ‘Songs Of Love & Lust’.

“What we were doing as Chris & Cosey came from finally being able to breathe and relax into our relationship,” says Cosey. “We had already been moving in that direction towards the end of TG and, oddly enough, Sleazy was on board with that. He loved melody, especially John Barry, but we wanted to go somewhere else with the skills we’d acquired from TG. So when we got to work on our own, it was quite a celebration. The freedom! Any spare time we had, we recorded tracks in the basic studio we’d put together at our house in London.”

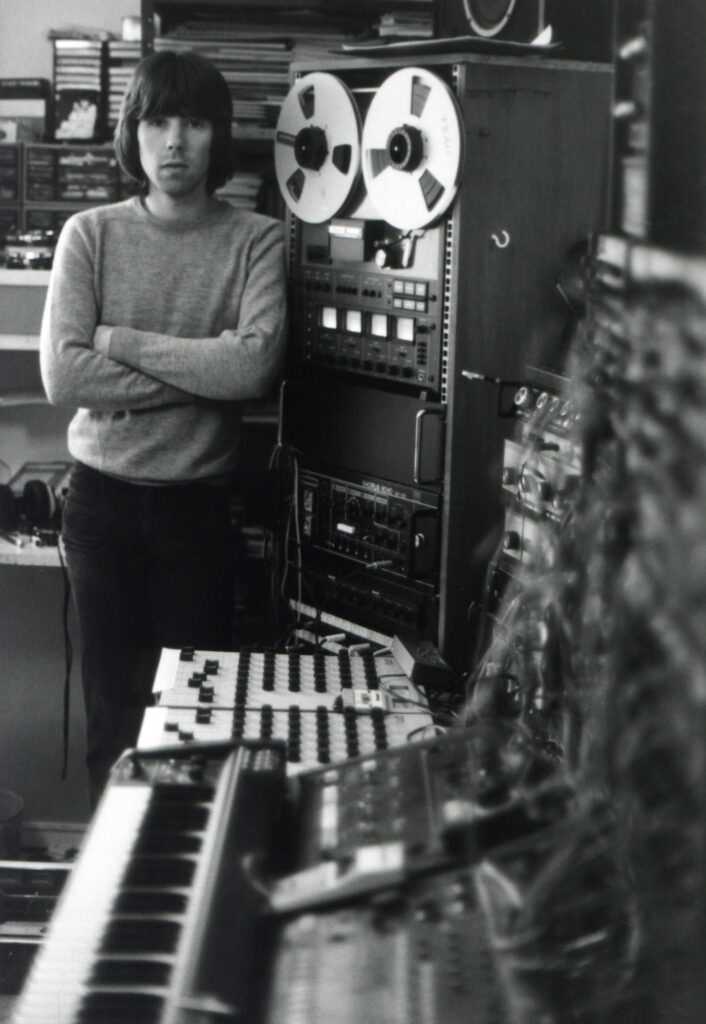

“We had to hire a lot of gear in TG,” says Chris. “As soon as we went out on our own, we bought a 4-track, then an 8-track. All of a sudden, we had the means to record on tap and ready to go at any time.”

“We were also on the crest of a technological wave,” adds Cosey. “MIDI was coming in and we started buying samplers, drum machines and other equipment. Before this, we’d have to wait for Sleazy to turn up, or see if Gen was in the mood, and the planning we had to do was quite restrictive. On our own, we could work whenever we felt like it, so we were recording all the time. And we’ve done that ever since.”

The release of ‘October (Love Song)’ as a single in 1983 encapsulated the poppermost end of Chris & Cosey, pulling together their various emotional strands into an artful paradigm of synthpop. By rights, it should have been a hit. The pair have no regrets on that score, though.

“We were asked to tour with loads of different bands – Depeche Mode, Blancmange – but it wasn’t really our thing,” says Chris. “We were offered a world tour with Grace Jones in 1981, but we turned it down. We were very happy, Cosey was pregnant, we were going to move out of London and settle down in the country, and we thought, ‘No, we don’t really need that right now’. We wanted to do it to our own timetable, not someone else’s. If we had taken that tour, our career path might have gone on a different trajectory. We’d have been exposed to lots more people and ‘October’ might well have been a minor hit…”

“But then we wouldn’t have been able to use those lyrics and we would have had to tone down the videos,” sighs Cosey. “We’d have felt we were being edited for the sake of business. And I’m not in a business. I remember John Balance once saying to me, ‘Have you heard this stuff? You could do it standing on your head. It’s what you’ve been doing for years’. But I saw the effect that popularity had on you personally, from when we worked with the Eurythmics. I saw what soaring to Number One did to you. And I wasn’t prepared for that.”

Cosey is referring to ‘Sweet Surprise’, a single the pair released under the name Chris ’N’ Cosey And… in 1985. It’s pretty obvious when you hear it, but performing on the track, totally uncredited, are the Eurythmics couple Annie Lennox and Dave Stewart.

“We had a mutual friend who said Annie and Dave wanted to meet up for a chat about collaborating,” says Chris. “This was in 1982. We knew who they were, of course, but they weren’t mega-famous. We all got on really well, we had lots in common and a similar sense of humour, so we went down to their small studio in Chalk Farm to try a few things out.”

“Dave thought we should do a track with a raunchy drive to it – something that a stripper might dance to,” remembers Cosey. “That style was totally different for us, but Chris played some synth and a bassline and worked out a rhythm using Dave’s new Movement Drum System, which he famously used for ‘Sweet Dreams’. I was experimenting with various dirty-sounding guitar riffs with Dave, and once Annie started going through different vocal lines, not lyrics as such, but using the unique and extensive range she’s become known for, the track started taking shape nicely.

“We didn’t get to finish it before ‘Sweet Dreams’ was released and went to Number One in the charts,” says Chris, picking up the story. “We were over the moon for them and we managed to get together a few more times to work on the track. By then, they’d moved into The Church Studios in Crouch End, where we did the final mix for the 12-inch. Dave suggested ‘Sweet Surprise’ as a title, because we’d recorded it while they were writing ‘Sweet Dreams’, but we hit a brick wall with their management after their sudden success and the 12-inch was shelved. Annie and Dave were determined it would get released though, so in 1984 we came to an agreement that Rough Trade could put it out if we didn’t use Annie and Dave’s names.”

“It was a little disconcerting watching them go from being regular people, friends of ours, to international superstardom so fast,” adds Cosey. “We saw how it affected them. It’s probably another of those subconscious reasons we’ve shunned that kind of spotlight over the years.”

There was also the matter of their young son, Nick, who meant infinitely more to them than being introduced on ‘Top Of The Pops’ on a Thursday night by Dave Lee Travis.

“We took Nick out on tour with us, but we didn’t want to play the really big venues,” says Cosey. “We weren’t looking for the limelight.”

It was an attitude that ran counter to the “entryist” philosophy of left-field groups like The Human League, ABC and Scritti Politti, whose pop ambitions were laced with a desire to infiltrate. While Chris applauds their intentions, he reiterates it wasn’t for them.

“Rough Trade had a lot of bands doing that, but we were their outsiders,” he says. “We wanted to tour on our own terms and I think everything worked out for us. We didn’t make a lot of money, but we did make a living doing gigs… hundreds of gigs.”

Chris and Cosey cemented their sense of autonomy by forming their own independent label, Creative Technology Institute, in 1983. They further underpinned their unusual credentials by working with the likes of Coil, Current 93, John Duncan and Robert Wyatt. Their determination to do something different also extended to their live performances.

“We did all the mixing onstage, alongside the playing,” says Chris. “When you look back at photos of our live shows, Cosey had guitar, cornet, drum and effects pedals, while I had keyboards, a tape machine and a mixer.”

“People used to say, ‘They don’t move very much onstage do they?’,” adds Cosey. “That’s because we were too fucking busy making the music! ‘If I start dancing around, the music’s going to stop, mate’.”

Amid the increasing homogeneity of 80s synthpop, Chris & Cosey retained a number of distinctive features, not least Cosey’s cornet, which functioned like “a call to arms, a hunting horn”.

“The cornet was an accident, really,” she says. “Sleazy had one but he couldn’t get a note out of it, he could only get a fart noise, so I showed him how to do it. It’s all about the puckering. So then I bought one because I liked the thought of my breath creating and shaping a sound.”

As the decade progressed and electronic music became more ubiquitous, Chris & Cosey found themselves shape-shifting to maintain their edge, their distinction. When they started using samplers, they utilised them for musique concrète-style field recording purposes, as evidenced on 1987’s ‘Exotika’ album, rather than pilfering riffs from soul drummers and the like.

“I remember sampling the gas tank in the garden here,” says Cosey. “It has a fantastic percussive sound. But I don’t remember responding to what was on trend at the time. What other people did was their thing. I admired it, but didn’t want to imitate it. Even now, if anyone nicks one of our sounds, I take it personally… ‘You lazy bastard, get your own thing!’”

“We have had a few run-ins with bands who sampled our work,” notes Chris, quickly closing down the inevitable follow-up question.

An even greater transformation in the ongoing electrofication of the UK music scene was rave, which spoke directly to Cosey’s need for a bodily relationship with sound. With tracks such as 1984’s CTI release ‘Dancing Ghosts’, featuring a Roland TB-303 and a TR-808, Chris & Cosey anticipated the squelch and bass rumble of acid house.

“When you play things like that live and you feel the sound so physically, that’s what really drives me,” offers Cosey. “Without it, it’s like a lukewarm cup of tea.”

“It’s just not enjoyable,” says Chris.

The video for ‘Dancing Ghosts’ may well have conjured up spirits from the past as well as the future. It was filmed in what they believe was a palpably haunted mill.

“I’ve never been so scared in my life,” exclaims Cosey. “It didn’t help that we had a strobe for the filming, which created after-images, and that fed into the whole ghostly vibe. I kept thinking, ‘Are these after-images or shadows from something or somebody else?’.”

“We were also possibly hallucinating,” deadpans Chris.

“Yeah, well, we won’t go into that,” says Cosey.

The duo’s development was blighted when Cosey was diagnosed with a heart problem that dogged her throughout the 1990s. The condition completely sapped her of any energy, which was an especially cruel blow given her artistic focus on the physical.

“The doctor who treated me was called Dr Roland,” she says, with a muted chuckle at the irony. “I must admit that I resented being ill. I’d been really physically active, going to the gym five times a week, bike rides, and then to be suddenly told I couldn’t do anything… I remember seeing a poster for a rave as I was driving home one day, and I thought, ‘Fucking bastard, I’m too ill to do that now’. I felt robbed. I’d have been in there all night long, just loving it.”

Not being able to tour blew a huge hole in the couple’s finances and it was two years before the doctors eventually found the correct balance for Cosey’s medication.

“It was good that my inability to breathe was at last taken seriously,” she says. “I used to have a hand fan, which I used to try to get a lungful of air.

I remember going to a pantomime with our son and having to go to the foyer to get air. I carried on because I was a neurotic, possibly menopausal woman. While I was ill, Chris suggested I do an Open University degree, studying fine art, and I got my degree around the same time I received my correct diagnosis. After that, my energy returned. I was back on the horse. I could breathe again.”

Electronic duos generally tend towards the yin and yang – Suicide, Soft Cell, Pet Shop Boys, Sparks. With Chris & Cosey, it’s more complex. Their close personal bond has made for more of an overlap between them. In interviews, they don’t quite speak in one voice – they qualify and sometimes correct each other – but there is a sense that, despite their differing characters, they are merged as a single entity.

“The overlap has come over time,” says Chris. “Cosey usually does the lyrics and melodies, and I do the basslines and rhythms, but that has become more blurred over the years, especially with the arrival of computers.”

Cosey says she often finds herself “dancing in my head” to the basslines and she’ll sometimes suggest a directional shift or an alternative emphasis.

“I think the difference with me is, I have an idea and I want it done now,” she offers. “I’ll be thinking, ‘Just fucking do it or I’ll lose the moment’.”

“It was quite polarised at the beginning, but Cosey has learned more about technology and I’ve encouraged her to embrace it,” says Chris, who admits to chipping in the odd melody in exchange.

With the dawning of the 21st century, the pair decided it was time to wind down Chris & Cosey. They adopted a new name, Carter Tutti, which coincided with a Throbbing Gristle reunion in 2004. Getting TG back together saw Chris and Cosey returning to their avant-garde leanings, recording fresh material and touring, first with and then without Genesis P-Orridge. But it was hard to make a clean break. For a few years, they were simultaneously Chris & Cosey, Carter Tutti and Throbbing Gristle.

“We’d been playing those Chris & Cosey songs for 20 or 30 years,” says Cosey. “And then suddenly those songs were in vogue and people wanted us to play them, but we’d moved on. We were in a different place, making different music. So we decided to call ourselves Carter Tutti, just so people wouldn’t turn up expecting us to do Chris & Cosey songs.”

“But then a friend of ours asked us to do a Chris & Cosey set at the ICA,” laughs Chris. “We agreed and it was crazy. It sold out. We did updated versions of the old material.”

Today, Chris and Cosey are busier than ever and as potent as ever, as their solo output attests. Their collaboration with Factory Floor’s Nik Void as Carter Tutti Void was another metamorphosis, an exercise in electronic sound and innovation that was a critical success, achieving something very distinctive even amid the mushroom cloud of 21st century electronica.

Chris is currently reworking his solo back catalogue material for Mute, with his ‘Electronic Ambient Remixes One’ and ‘Electronic Ambient Remixes Three’ albums from 2000 and 2002 scheduled for reissue as a double vinyl set in the summer. There will hopefully also be some more live interventions along the lines of his improvised analogue performance at the Surrey Moog Symposium in 2018.

Cosey has meanwhile contributed the soundtrack to the Caroline Catz film ‘Delia Derbyshire: The Myths And The Legendary Tapes’ and is now writing a follow-up to her ‘Art Sex Music’ biography. The book, which will be published in 2022, further explores the obstacles and abuse faced by women, with Cosey meditating not just on her own life and work, but also looking at the likes of Delia Derbyshire and the 15th century mystic Margery Kempe, who wrote what is said to have been the first autobiography in the English language.

The last hurrah for Chris and Cosey as Chris & Cosey came in the summer of 2019.

“We did our final live performance as Chris & Cosey,” says Chris. “It was part of the Subliminal Impulse festival in Manchester. The venue was rammed, totally sold out, and there was so much love in the room. It was such a poignant evening. Maybe because the audience knew it was our last gig.”

With a set that included ‘October (Love Song)’, ‘Lost Bliss’, ‘Dancing On Your Grave’ and ‘Love Cuts’, the gig was Chris & Cosey in essence. With each track an electronic strobe light cutting through the underground darkness, arch and sultry, mechanical but physical as fuck, this was a reanimation of the immaculate dancefloor sleaze of the late 20th century, in which nothing was spared for the sake of pop politeness. The audience, which one reviewer described as “made up of the young and old, the strange and weird”, loved every minute.

“I remember feeling sad onstage,” says Cosey. “Knowing it was the last gig for us as Chris & Cosey and knowing that everyone in the crowd was ecstatic to see us… but then also knowing I would never feel like that again and neither would they. It was sad and euphoric at the same time.”

Although Chris & Cosey may be no more (maybe), Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti are still very much with us – revisiting the past and contemplating the future.