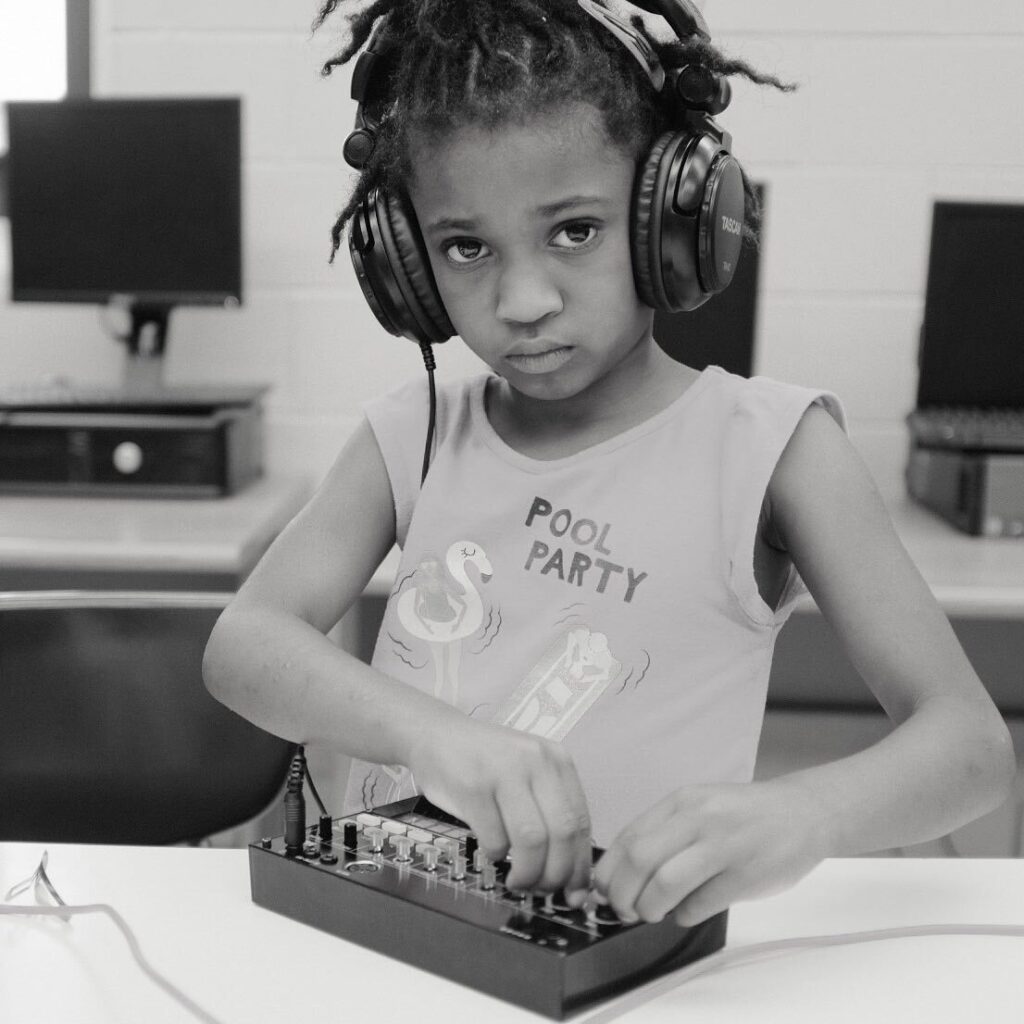

If you like synths and changing the world for the better, it’s time you became familiar with AFRORACK, an initiative using modular synthesis to improve access to technology among disadvantaged groups. We caught up with founder Aaron Guice to hear more about the organisation’s latest project – AFRORACK London

Hi Aaron. Can you tell us about AFRORACK and how AFRORACK London came about?

“AFRORACK is essentially a STEM-focused curriculum based around modular. Its whole creation is to fulfill a need for access for people of colour – mainly here in America, of course – but after starting in Chicago we recently expanded it to London, which is really, really cool. In terms of how AFRORACK London actually came about, during Covid people from all around the world were reaching out to me to come and teach. I had to figure out a way, and at first we thought about setting up in Berlin. That made sense, but looking at the map and looking at access to the rest of the world, we thought that that London and the UK was the better choice. It’s an amazing place – you have access to the EU and you can get to Africa pretty easily. And I speak English, so it’s much easier for me to teach!”

How does the UK compare with the US in terms of access to technology?

“I went to the UK with a completely different idea of what it was like, but when the expansion to London happened, I saw a very different need in the audiences. In the UK, everyone essentially shares the same space, and access is much more based around class. I wasn’t expecting everyone to be experiencing the same circumstances! It’s a little bit different here in the States, where those things [race and class] kind of go hand in hand. Alongside that, the music is different, the mixtures are different. It’s just incredible to be around these folks, and so many kids that are first generation from Africa and the Caribbean.”

Did those differences mean you had to reimagine AFRORACK workshops for a UK audience?

“AFRORACK originally stemmed from my experiences here in the States, but my experience in London has basically shaped the future of where this whole organisation is going to go. In recognising that void – that people of all different backgrounds are actually sharing the same issues relating to either poverty or economic status within their society – it has spawned a whole new idea. One of AFRORACK’s main curriculum has been called ‘Think Modular’, and we’re leaning into that as one of the family of brands for this current season. That’s because we have to open the courses up and make it more expansive, including people who are white, and really anyone who doesn’t have access, because it’s about whether the individual, the school, or even the area, can afford it. We spent some time going up to Scotland this last time we were out in the UK, for example. Leaning into ‘Think Modular’ is super-duper important, not only for the future of access, but the future of what I’m doing.”

You’ve already touched on some of them already, but what do you think are the biggest obstacles in terms of people’s access to technology?

“It all comes down to money and economic circumstances, and those circumstances can be shared by so many different folks, regardless of the colour of your skin or background. Even if you give someone an instrument, we found that there’s a lot of things that are happening at home, that are keeping the kid from continuously being in that creative space mindset. You know, we can’t go around curing poverty at home, so while we might host our workshop in very creative spaces, when the kids do go home, they still have to deal with their own specific set of circumstances, meaning that freedom to think and explore often starts and ends with our classes, unfortunately. That’s more of a systemic issue, and we can only solve so much, but giving people the space to actually be creative, even if just for that moment, is super cool.”

It sounds like you’re describing some of the potential effects of cultural capital...

“Yeah, absolutely. Speaking to that point, I had to get on the phone and convince a first-generation Nigerian father that having a son come to the AFRORACK workshop after school was probably as important as him studying for his SATs. He was keen for his son to study for the tests so he could become a doctor or lawyer or something like that. But this kid had pretty exceptional engineering skills and a great interest in STEM. Me getting on the phone to the father helped a lot, but these are just some of the pitfalls that you have to overcome – it has to make sense to people.”

What happens in a typical AFRORACK workshop?

“People reach out to me all the time through email asking about this, and I try to stay away from a specific answer, because I want to give people the confidence to create their own curriculum! It’s such a wide open space and there’s so much stuff that’s undiscovered, that it may seem like a shortcut or easier to look at what I’m doing as a blueprint, but there are possibilities beyond what what I do.”

What kind of possibilities?

“The possibilities of creating a curriculum that suits different spaces, different people, different groups, different subgroups. I struggle with not providing a clearer answer, because I’m a very open person and I like to create inclusive spaces and help people with their vision. But at the same time every space is so different, as I found out when I went to London.”

So you don’t want to define the future of this kind of work when others might choose to take a different approach?

“Exactly. I mean, the one thing I just really want is for people to have the confidence to be able to create for themselves, and I think it’s completely possible. I want people who come to AFRORACK to find a space for reflection, a space where people can visualise themselves in the future… and ultimately it’s a safe space to fail. People of colour rarely get the chance to fail, and anyone who doesn’t have the resources to start over again. People are so afraid to fail – they think they only get one chance, and that’s just not true. Through our workshops people realise that it’s OK to fail and it’s OK to transform. It’s something even we’re currently doing – AFRORACK isn’t gone, but ‘Think Modular’ is coming to the foreground as we aim to include more people.”

Have you found much outside support for your projects?

“Moog and Reverb Gives have been the two biggest supporters of AFRORACK. Moog was the first company to ever give me enough machines to actually go out and do the workshops – and of course we’ve been able to do AFRORACK London thanks to Reverb Gives. They have done an exceptional job in helping us outfit both our Chicago and London locations, and through them we were able to get a bunch of amazing instruments which are still there for the kids to access. It’s a phenomenal programme, and the way it works is that a portion of every purchase on Reverb goes into a pot for Reverb Gives, which in turn gives us access to whatever we want. We’re not the only ones benefitting from Reverb Gives – there are projects all around the world who are.”

What’s next for AFRORACK/’Think Modular’?

“We have some great stuff coming up. I’m going to Portland in a few days to work with some homeless youth, which is something very different to anything I’ve ever done before. It’s more based around that idea of economic circumstances that I was talking about and forms part of a bigger project that I’m working with the Portland Institute of Contemporary Art. The month of February is always very important for us, because it’s Black History Month. It’s a really, really amazing time to not only look back at things like the civil rights movement and where we’ve come from, but I also like to use that time as a moment of planning for the future, getting your ideas in order so you can use the resources in your neighbourhoods… visualise beyond what you think is possible. I’m also really, really excited about another project, but I can’t share it. I think the only thing I can give you is that AFRORACK has now partnered with arguably the biggest tech company on the planet…”

I’ll try and work that one out later…

“I’ll be making an announcement on that on in late February or so. It’s going to be major and will signal an even greater shift towards STEM education globally. We’re just really excited to be causing that shift and being able to usher the kids into the future.”

To find out more about AFRORACK, go to afrorack.org

To find out more about Reverb Gives, go to reverb.com/reverb-gives